|

International

Logistics

Soon

after our arrival at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio in 1974, my

boss at Headquarters, Air Force Logistics Command, Deputy Chief of Staff

for Materiel Management (HQ AFLC/MM), Major General Jerry Post, told me

that if I did a good job as his Exec he’d let me seek a new job with one

of his colonel directors, if they agreed, after 18 months.

Of course, I suspected that if an exec didn’t

do a good job for him, that move could happen sooner….

I

found an early interest in the fast-growing and innovative security assistance

business, which for AFLC included providing training, supply and munitions

support, depot maintenance and many other services to foreign air forces

that had bought, been granted, or otherwise received aircraft and other

systems used by the USAF.

Most

exciting to me of our fast-spending customers were the Iranians and Saudis,

and smaller but oil-rich Persian Gulf

sultanates and sheikhdoms, along with the many European and Asian nations

eager to co-produce the new F-16 fighter.

Also,

I was an unabashed fan of the most enthusiastic and creative iconoclast

among Maj Gen Post’s directors, Colonel Bill Stringer, Director of International

Logistics, even though I saw Maj Gen Post chew him out a few times for

excessive creativity.

To

my good fortune, as the 18-month point approached in 1976, these two officers

also agreed to start up a security assistance training program for young

officers to learn the business of supporting friendly air forces. My request to join this program was easy for

them to approve.

The

training program brought in roughly ten captains to learn by doing, to

be followed by assignments in the business.

This was a fun group of young officers, and we enjoyed learning

together.

Off to Cairo

Not

long after I joined, our Division Chief, Lt Col Gene Vallerie, walked

in among our desks and dropped a surprise, “Who’d like to go to Egypt?”

While

most hesitated to assess this intriguing question, one other fellow and

I immediately stood up and said, “I would!”

Shortly, I had temporary duty orders for what would become seven

exciting months in Cairo. The duty title would be In-Country Program Manager

for the first USAF Foreign Military Sales program with Egypt in 25 years:

sale of six C-130H transport aircraft, with aircrew and maintenance

training and supply support.

I

was a rank beginner at what I was about manage.

But, in a career pattern already emerging, which resulted over

time in my becoming fully-qualified in six different USAF career fields

while being formally trained for three weeks in only one of them, I dove

in enthusiastically. And it worked

out just fine.

This

short-notice requirement had arisen during the Senate hearing on the sale.

Building

a new American relationship with Egypt

was important to our nation, especially this soon after President Sadat

had thrown out his Russian military advisors and fought the 1973 War against

Israel.

To

date, as steps in building a new post-Soviet relationship with Egypt, President Nixon had given his Marine One

helicopter to President Sadat, and the U.S. Navy had provided support

in clearing the Suez Canal of ships sunk

there during the ’73 War.

A

logical next step was to begin some military equipment sales. But it was understood at this point that our

political system wasn’t ready to sell Egyptians things they might decide

to use in shooting at Israelis. Thus,

appropriately--and with Saudi

Arabia paying the bill to keep things

easy for the Egyptians--arose the widely-used and well-proven C-130 Hercules

transport aircraft.

During

the Senate Armed Services Committee hearing about the C-130 sale, Senator

Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota noted that the Lockheed Corporation, manufacturer

of the C-130, had been caught bribing foreign officials--including bringing

down a prime minister of Japan.

Egypt, as with many developing countries,

was known for baksheesh--“share the wealth,” said by beggars on the street

but also applied to bribery. Senator

Humphrey requested that the Air Force place a government person in-country

between Lockheed and the Egyptians. That

turned out to be Captain Eckert.

As

everything about this assignment was new for everyone, I was told to plan

on a six-month temporary duty (TDY) in Cairo,

after which next steps would be determined.

Sue

and I agreed that she would fly over to join me, since we correctly assumed

that, on my TDY per diem payments, the two of us could live more cheaply

in an apartment than I could alone in a hotel.

It would be an adventure for both of us.

Rightly

figuring that learning some Arabic would serve us both well, we bought

a small English-Arabic dictionary. We

taped little labels onto things all over our three-bedroom house in what

formerly had been an Ohio

cornfield, and began to blend Arabic phrases into household conversation. However, our St. Bernard, Daisey, didn’t appreciate

having “kalb” taped to her forehead, and promptly removed it.

Appreciating

that many last names in all languages have a literal meaning (Eckert is

old German for a person who lives on a corner, an “ecke”), I was amused

to think that Arabs watching American TV might see Vietnam-era newsman

Bernard Kalb as Bernard Dog. Why,

if he were canonized some day by the Catholic Church, he’d be perceived

by Arabs as much like our Daisey! (Saint Bernard Dog) Like most

beginning students of a language and the associated fascinating historic

culture that we barely comprehended, we enjoyed these polyglot diversions

(and understand that Mr. Kalb isn’t Catholic…).

I

was made a member of the 13-person USAF pre-activation review team sent

to Cairo under the leadership

of the widely-respected Colonel Cary Broadway--to assess requirements

for the C-130 sales package and Egyptian basing arrangements. In an early survival lesson that was to serve

me well later, I noted that, of the people on the team, during our brief

time in Egypt

all got food poisoning except for the three members who appeared to polish-off

a bottle of scotch together every night.

In

a related lesson, I was later told by one of our contractor-support C-130

mechanics that a reliable key to getting through Egyptian customs quickly

at Cairo International

Airport was to slip

a bottle of scotch to your customs inspector.

After

Sue joined me in Cairo,

we stayed briefly in the Embassy Guest House while looking for an apartment.

There, we had fascinating conversations with other government travelers,

including some visiting USAID doctors who shared surprising observations

such as: (1) don’t eat fish in Cairo--the country’s transportation

system apparently couldn’t get fish from the Red Sea to the table without

spoilage, (2) while visiting hospital emergency rooms, they saw one doctor

accidentally drop his stitching needle onto the floor, pick it up, and

proceed to stitch a wound, and (3) other than those stationed at military

hospitals, there appeared to be no ambulances in the city--which helped

explain while, during my first three months in the city, I personally

saw five dead pedestrians in the street--and was told that the corpses

got moved when a family member came with some form of vehicle--often a

taxi.

Staff

Officer in Headquarters, Egyptian Air Force

I

learned that my primary work location would be an office in Egyptian Air

Force (EAF) Headquarters, between the offices of two Egyptian two-star

generals: Major General Rayan, Chief Engineer (who oversaw

procurement), and Major General Bashary, Chief of Logistics. They were impressively hospitable to this new

presence between them, as were Brigadier General El Tawil, EAF Chief of

Maintenance, and Brigadier General Shetta, Chief of Training. All were willing to talk at any time when I

needed advice, and were very understanding and patient as we brought our

two Air Forces’ cultures together after 2½ decades of little or no communication.

Years

later, after he retired from the EAF, General Rayan became Chairman of

EgyptAir, the national airline. On October 31, 1999, EgyptAir Flight 990 crashed into the Atlantic Ocean about 60 miles

south of Nantucket Island,

MA, killing all 217 people aboard. Media coverage showed General Rayan’s deep personal

involvement in the international response to this tragedy.

My

assigned counterpart in the EAF was the wonderful Lieutenant Colonel Rafaat

El Gamal (“Bill, that means Rafaat Camel”).

Together, Rafaat and I teamed to make this important adventure

work for our Air Forces and our countries.

While getting a lot of new things done together, we developed close

mutual respect and friendship. We

shared each other’s victories and frustrations with our respective bureaucracies,

as we taught each other what worked and what didn’t.

Much

of this work was hard, as we constantly had to explain to other Egyptians

why the American way of doing things was different from the Soviet way

they’d been taught for 25 years. As

our American team worked to train the appropriate Egyptian pilots, maintenance

and supply personnel about how to fly, maintain and support the C-130,

I was constantly reminded that this was their country and their Air Force,

and that they’d deal with the C-130 as they saw fit.

Of course, they were right.

We on the American

team regularly had to decide where to draw an appropriate line between

respect for their sovereignty and pride…and safety of their procedures

with the C-130, so that somebody wouldn’t get killed. It was clear to me that, for their part, the

Egyptians were constantly reminding themselves to be patient with us Americans,

as we were so ignorant of their culture and of the procedures that worked

for them with their Soviet, French, et al aircraft.

Fortunately,

everyone wanted this program to work.

Everyone wanted our two Air Forces and our two countries to build

a lasting friendship. And the Egyptians

I met, as a group, were naturally hospitable and truly friendly people.

Indeed,

it was a frequent occurrence out on the streets of Cairo to be stopped by someone, usually a male

student, and asked, “English, Russian or American?” When I answered, “American,” the hand would

shoot out to accompany an enthusiastic, “Welcome back. We always thought that your Secretary of State

John Foster Dulles and our President Nasser made a big mistake in deciding

that our countries shouldn’t be friends. We know American movies. We know American politics. We wear American blue jeans. We’ve always liked Americans. And, frankly, nobody liked the crude and pushy

Soviets who came here.”

The

work and friendship and progress made with Rafaat and his Air Force became

the highlight of my seven-month experience in Egypt.

The Egyptian Air Force C-130 Squadron

strapped a Lockheed mechanic who was an amateur photographer onto the

open ramp of a second, leading C-130 to get this photo, which became a

popular Lockheed poster shot. I

suggested dipping between the Pyramids to get the appearance of flying

out of a Pyramid. It worked.

Not

to say that we lacked surprises. A

few stories about interesting cultural differences that we dealt with

together:

One

day, our Egyptian C-130 Squadron Commander, Colonel Hamza, kindly invited

me to ride in the jump seat on a local training flight. After we strapped-in, I enjoyed watching the

two pilots go through the normal steps of starting up this beautiful new

aircraft. But, as we taxied out,

I had to ask Hamza a question. “Sir,

when an American flies a C-130, he’s required to use a checklist to make

sure that none of the required steps are missed.

I notice that you haven’t used the checklist, and would like to

ask why?”

Patiently,

since he knew I wasn’t a pilot and therefore didn’t know much, the Colonel

answered, “Bill, a pilot who knows his job shouldn’t be reading a book

when he’s trying to fly the plane.”

I

had no answer for this elegantly-simple reply.

One

day, Colonel Hamza asked me if I knew what electric motor was used in

a certain General Electric refrigerator, because he needed to get one. I said I didn’t really know anything about that

motor. He replied, quizzically,

“I don’t understand. You’re an

American, and it is made in America.…”

Life

on the flight line had its moments of excitement. One day, I watched an Egyptian soldier, standing

way up on a well-worn old maintenance stand, hanging on the end of the

great big wrench (about four feet long) used to remove the nuts that hold

the Hamilton Standard propeller onto the C-130’s big Allison turboprop

engine. To my surprise, the maintenance stand didn’t

have the “normal” (to us) waist-high safety railing around the top, but

only a pipe about ten inches up from the man’s feet--just high enough

to catch his foot if the wrench slipped, assuring that he’d fall to the

concrete below head-first.

One

day, I watched an Egyptian do liquid oxygen servicing on one of the C-130s.

The little truck carrying his big LOX tank and hose had no gas

cap, and you could have stuck your fist down into the gasoline.

Meanwhile, the hose fitting didn’t fit squarely onto the aircraft’s

LOX access connector, so a 15-foot geyser of LOX was shooting into the

air. The Egyptian LOX technician watched this with

complete relaxation--made evident by the fact that he was smoking.

Another

day, one of our mechanics asked me for help in convincing the Egyptians

to change the tires when they wore down enough that red safety warning

band began to show.

I

had to go talk to Brigadier General Sobhy El Tawil, the brilliant EAF

Chief of Maintenance and former test pilot who always taught me a lot

about how things worked in his country.

I asked him if he might consider establishing in the C-130 squadron

what we Americans called a safety program, with an appointed safety officer,

to help people look for things we could do to make the working environment

safer for his people.

He

smiled patiently, and said, “Bill, I understand exactly what you are talking

about. But we won’t be doing that.” He explained that there were a number of interwoven

factors in this decision. First,

he said, Moslems believe in pre-destination: if something happens, it is the will of Allah.

Second, he said, since the debacle of the 1967 War, when the Israeli

Air Force destroyed the EAF on the ground in four hours, while respecting

the Army many Egyptians did not respect the EAF.

Thus, many soldiers brought into the EAF--even in 1976--had disciplinary

issues ingrained by their parents. So, if such a soldier were hurt on the flight

line, and the C-130 Squadron had a safety officer, there’d be a tendency

for the soldiers to blame the safety officer.

From the perspective of maintaining discipline in the unit, it

was better for the soldiers to have to take care of their own safety.

When

I asked him if he would instruct the C-130 squadron’s maintenance people

to please follow the tech orders for things like changing worn tires,

he again patiently explained. “Bill,

you come from a wealthy country. We

are a poor country. My engineers

have calculated that we can safely get more landings from those tires--so

we’re using our brains and saving money.”

I said, “Don’t you think that the people who manufacture the C-130

and its tires know more about them than your engineers?”

And I asked, “With this approach, can you tell me that you’ve never

lost an entire aircraft in a crash, due to a blown tire on landing?” He admitted that the EAF had experienced such

a loss, and thanked me for my enthusiasm about their safety. But there would be no safety program.

I’d

been working hard at learning more Arabic, and wasn’t shy about trying

my small vocabulary on fellow officers.

Of course, they regularly laughed, which was fine as long as they

then helped me.

One

day, Rafaat came to me with a sheepish look on his face. He said, embarrassed, “Bill, it would be better

if you don’t try to learn more Arabic.

There are people who think you’re a spy.”

Sue

and I had noticed individuals sitting in cars down the street from our

apartment for hours, looking straight at our building. I wondered about them, but left it alone.

Then, for my birthday on April 15th, Sue took the initiative

to invite the Egyptian junior officers I worked with, and their wives,

along with many of our American team members. We agreed that this would be a nice way for

the two groups to get to know each other better.

Of

the many Egyptians invited, only Rafaat and his wife Sana came. Again

embarrassed, but again a good friend, Rafaat quietly told me that he was

the only officer allowed to come. Apparently,

there was concern about this American officer trying to somehow compromise

the Egyptians. A disappointment,

but I understood. They simply didn’t

know us yet, and we all had to go slowly.

One

day in July 1977, Colonel Hamza asked me to not come out to the C-130

squadron for at least a few days. I’d

read in the papers about a steadily-building confrontation between Libya’s

leader Muammar al-Gaddafi and Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat, as Gaddafi

had maintained close ties to the Soviets, had been working to undermine

Sadat’s policy of peace with Israel, and in June had ordered the 225,000

Egyptians working in Libya to depart the country.

Egyptians returning from Libya along

Rommel’s Road--the level one along the Mediterranean shore west of El

Alamein, as opposed to the roller-coaster road of paved dunes built by

Field Marshal Montgomery’s British army east of that great battlefield--where

today you see beautiful national cemeteries, including a German one.

Anticipating

the possibilities for the C-130s, I remarked to Colonel Hamza to please

keep in mind that landing on sand with thrust-reverse could cause a lot

of damage to the turbine blades in the C-130’s Allison turboprop engines.

Starting

about July 19th, after Egyptian border guards had halted a

Libyan “march on Cairo” to protest Sadat’s peace policy, Libyan tanks

and aircraft raided across the border into Sallum, Egypt, supported by

artillery fire.

What

followed was a brief border war, in which three Egyptian Army divisions,

supported by the EAF (including our C-130s), bombed and captured Libyan

border towns. An armistice was

declared on July 24, and we Americans were quickly invited back onto the

base. There was significant engine damage….

I

got another lesson on the doable--as opposed to ideal--pace of things

after seeing Rafaat literally crying in frustration over his failure to

gain more progress in administrative matters with the C-130 program.

The

Egyptian military was used to the Soviet system, wherein they made few

decisions themselves, and the Soviets issued them what Soviet standards

said they should get. Interestingly,

as one Egyptian told me, this included the MiG squadrons that arrived

with a full supply of parkas.

As

I saw it, Rafaat’s superiors were leaving most of the work in the Headquarters

that related to working with the Americans to Rafaat. And they didn’t yet understand or want to grasp

that the American system included letting the receiving country make a

lot of decisions for itself, which the Americans would then respond to

and support.

For

example, after I taught myself how to use the USAF supply requisition

system (you do what you have to do…), I then taught it to the Egyptian

supply people. During this course,

I showed Major General Rayan a computer punch card and a sample supply

catalog. I explained that each supply item had a National

Stock Number (NSN), and that if his supply people punched that number

and some other information into a card and gave it to me, that item would

be sent to Egypt.

I

remarked to General Rayan that there was a NSN for a fire truck, and if

he wanted a fire truck, it would take one card to order it.

The

General’s eyes got big. Remember,

this was the officer who had our one Xerox machine in his office, so that

he could question anyone wanting to make a copy, as Xerox copies were

expensive. He said to me, “Captain, maybe it’s not such

a good idea to teach these things to my people.

I don’t want them ordering fire trucks.”

Rafaat

couldn’t do it all. And we both

knew that our two Air Forces had many new things to do together in the

future. I shared his frustration. And it was my job to do something about it.

I

typed a carefully-worded two-page memo to General Rayan, explaining that

I believed our two Air Forces wanted to build a future together, and pointing

out some obvious steps that each of us needed to take.

I

gave the signed original to General Rayan’s Exec late in the EAF work

day, and then took a copy to the Embassy for our Defense Attache to read.

The

Attache, a wonderful brigadier general who went on to multiple stars,

laid the letter on his desk after reading it, and said, “Bill, can you

get this letter back before General Rayan sees it?

If he reads it, he may ask that you be sent out of the country.”

I

was shocked. I told the Attache

that I stood behind every word in that letter.

It was fact, and it was obvious.

He said, “I agree with you, but the Egyptians aren’t ready for

this yet. The problem here is that

you are pushing to make progress in this program faster than they want

do, and you can’t do that. You

need to step back. They will run

the EAF the way they want to, and you are not going to change that.

Go get that letter back before the General sees it.”

I

was able to recover the letter. I

was not thrown out of the country. And

I understood what very good advice the Attache had given me. I should have coordinated it with him first.

It still hurt to see opportunities missed or delayed--and to see

my friend frustrated.

But

the EAF C-130 program did go on successfully.

And I learned a valuable lesson.

The

following year, on February 19, 1978, the EAF lost the first of our six

C-130s.

Two

terrorists had killed Egyptian newspaper editor Youssef Sebai at a peace

conference in Nicosia,

Cyprus, taken hostage 16 other Arabs,

and demanded and got a Cyprus Airways DC-8 to escape with their hostages.

But after Djibouti, Syria

and Saudi Arabia refused

to let them land, they returned to Nicosia’s

Larnaca Airport.

Syrian president Kyprianou went to Larnaca himself to oversee negotiations

and the Cypriot National Guard troops surrounding the airliner.

Meanwhile,

Sebai’s friend President Sadat put Egyptian commando Task Force 777 onto

a C-130 and flew them to Larnaca. Right

after the C-130 landed, the Egyptians raced out of it and toward the DC-8. The Cypriots warned the Egyptians to stop and

return to their C-130, were ignored, and opened fire on them. In the heavy firing between Cypriots and Egyptians--while

the terrorists watched--in addition to killing 12 Egyptian commandos the

Cypriots put a106mm anti-tank missile into the nose of the C-130, destroying

it and killing three aircrew members.

Following

this tragic and completely unnecessary display of bravado by the Egyptians,

they learned that the Cypriots had already negotiated the surrender of

the two terrorists, whom Cyprus

later extradited to Egypt

for trial.

What

a stupid waste of brave men….

Cars

in Cairo

In

1976, Cairo

was a fascinating place to live, but also a hard and often dangerous place. Especially when you got onto a road.

By

the way, although there was much poverty in Cairo, known as “a city of ten million people

with housing for six million,” Sue and I always felt safe walking in the

city, and never had a single issue with crime.

I credit much of that to Islam, and to the general courtesy of

the Egyptian people.

When

you see a TV journalist reporting from Cairo,

you’re often seeing them on the roof of the Nile Hilton, with the river

and Gezira Island

in the background. If you listen

carefully, you can also hear the constant honking down below. Egyptian drivers follow the Italian nanosecond

rule--that’s the time between when the stoplight turns green and the driver

behind you begins honking. Egyptians

also honk for essentially every other movement, change in direction, or

new thought entering their heads while driving.

Among

our Egyptian friends living in our apartment building in the suburb of

Heliopolis, across the street from the Merryland Gardens

park, and not far from EAF Headquarters, were a veterinarian named Magdy

and his wife. Magdy had served

in the ’73 War as an Army doctor…after all, he’d gone to vet school in

Germany, and was

very good.

Magdy

appreciated that our rental apartment had a refrigerator. He had ordered one--reportedly the only brand

made in Egypt

at the time, since tariffs on imported appliances were so high--but they

had to wait a year to get it. When

theirs arrived, they invited us to come celebrate with them.

Magdy

was a pleasant, soft-spoken guy, very patient and generous in helping

us overcome our general ignorance of Egypt. He taught us, among other things, about driving.

Egyptians

drove as fast as possible. Even

soft-spoken ones. Like 60 mph on

residential roads that had cars parked on both sides and kids playing

soccer in the middle.

One

day, after Magdy had bumped a young soccer player while sailing by at

high speed, he felt bad and told Sue about it, “I did everything I could: I honked my horn.”

In

our arrival orientation briefing, the Embassy staff told us to definitely

rent a car with a driver, and not try to drive ourselves in Egypt. “If you have an accident, no matter who did

what, you’ll be held responsible. And

if you hurt somebody, it’s likely that a mob will gather and beat you. You’re a foreigner…and worse, an infidel.”

So

my driver was Taisir Tawil. Much

as half the people in Korea

appear to be named Kim, in Egypt

there are a lot of people named “tall” (tawil) if not “camel” (gamal)

such as my friend Rafaat and former President Gamal Abd El Nasser. Don’t even ask me about people named “Mohammed”….

Taisir

was a Palestinian who ran a little car rental business that transported

a number of the people on our C-130 team of government, Lockheed (C-130),

Allison (engine), and Hamilton-Standard (propeller) people.

The

Lockheed contractor team lead, a much older man named Jim with long experience

in aircraft maintenance, made sure that Taisir gave him a better car than

I had, to demonstrate his importance, so Taisir gave him a Mercedes while

I rode around with Taisir in a well-used Corolla.

Hey, it made Jim feel good…and that was part of my job, too.

Taisir

drove fast. One day, he had a soldier

on the hood. Another day, as we

drove down a major avenue, another car came sailing out of a side street

and T-boned against my door.

When

I asked why drivers routinely ran red lights, Taisir explained to me that

people are a lot smarter than lights.

“That red light doesn’t know that nobody’s coming the other way,

so why should a person just sit there waiting for it?”

Most Egyptian drivers obviously agreed with Taisir.

At

the end of one very long day, as we drove home through the darkness, I

asked Taisir why everyone drove at night with only their parking lights

on, but then flashed their brights at approaching cars just close enough

to blind them.

Carefully,

as if he were answering the stupidest question he’d ever heard, Taisir

explained, “We drive with the parking lights so we don’t waste electricity--we’re

a poor country, you know. But to

be safe, we flash the brights to make sure that oncoming drivers see us.

Mr. William, does that not make sense to you?”

Of

course it made sense. I didn’t

even try to argue. On we drove

at high speed in the darkness, occasionally hitting unseen fragments of

cinder blocks used as soccer goals and left in the street by kids in every

neighborhood.

When

it rained once or twice a year, Taisir would take the wiper blades out

of the glove compartment, mount them, and clear the mud off the windshield. “You can’t leave them out there year-round,

you know Mr. William, because the sun destroys them.” Of course, he was right.

In

a city that has dust everywhere, dark clouds create falling drops of mud. Interestingly, with all the donkeys, sheep and

camels in the city in 1976-77, adding their dung to the swarms of careening

cars, blue-cloud-belching trucks, and city buses so crowded that people

literally hung out the doors in groups, the dust that filled the air had

a flavor.

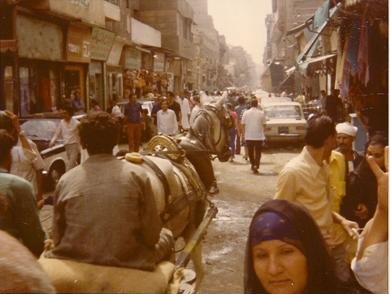

City bus in Cairo, 1976

By

noon most days, my freshly-laundered shirts had a dark ring around the

collar.

When

Taisir went on vacation for two weeks, I convinced him that he could save

the cost of hiring another driver by letting me drive myself. I explained that I’d learned to drive in Washington, D.C.,

which was designed by a Frenchman, and that I could take good care of

his car. After carefully balancing

the risk and obvious reward, Taisir agreed.

During those two weeks, driving defensively but purposefully, I

was in contact with other vehicles three times.

When Taisir returned from his vacation, I was very glad to see

him.

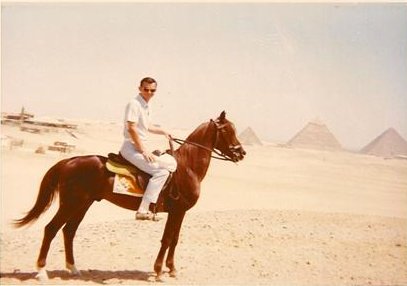

The

stable by the Pyramids had retired race horses. One touch of the heels,

and this fellow was at a full run.

Eating

Having

started learning basic Arabic words and phrases before we left Ohio, Sue

rapidly became a shopping advisor for the small group of American women

who lived within walking distance of our Heliopolis apartment--which happened

to be just down the sidewalk from a building with a sign that, as I recall,

said it was the regional office of the Sinai Multinational Force and Observers

(whose main headquarters is in Rome, Italy, interestingly).

Shopping

in Cairo in 1976 was so different from

the normal American experience that, right after returning to the USA after three months, for a C-130 program review

at the big Lockheed complex in Marietta,

GA, I went straight to an

American supermarket just to gawk at the fabulous wealth of food on the

shelves.

In

the basement of the U.S. Embassy (an hour from our apartment) was a small

room they generously called a “commissary.”

It did have nice butter and some cheeses from Denmark. And some packaged meat products from Germany. And a few boxes of cereal that had gone many

years out of date in the military commissary up in Athens

and were dumped on us in Cairo. Even a cereal lover like me has a hard time

choking down stale cornflakes. So

Sue got almost all of our food on the economy.

Fruits

and vegetables grew wonderfully in Egypt. Sue bought navel oranges the size of grapefruit

from donkey carts that came down our street—for the equivalent of two

cents each. Onions, which still

are a big export crop for Egypt,

were practically free. Whatever

we needed in these categories came right to our street on the carts.

Sue buying vegetables, right in front

of our apartment building

Meat

was another matter.

You

went to a traditional butcher shop. With

no refrigeration. Because of this,

the government wisely restricted meat sales to certain days of the week. What you sought in the butcher shop was hanging

on hooks from the ceiling. Half

a cow inside. A few split goats. A row of slaughtered sheep outside along the

sidewalk. No pigs….

You

pointed to the general area of meat that you wanted from the carcass,

and the butcher’s big knife would fly through the air and “thunk” into

it. You got the red meat, the viscera, and the flies.

This colorful chunk was wrapped nicely into newspaper and handed

to you…warm…to take home.

Sue in the entrance to our local butcher

shop.

You

don’t appreciate what the butcher in Kroger’s Meat Department does for

you until you have to wrestle and saw the viscera out of beef yourself. Especially when, for the same dinner, you must

boil all vegetables and soak all salad contents in bleach to prevent feeding

salmonella to your family and guests.

Of

course, we boiled all drinking water…and ingested no local dairy products

at all. I enjoyed filling a glass

with water and looking at it. Sometimes,

the little dots floating around in that water were swimming on their own.

Preparing

a meal was so laborious that, when a new couple arrived in our apartment

building, and the wife immediately announced that she wanted to cook dinner

for the other Americans in the building, the other wives insisted that

they each bring a dish--since preparing that much food was simply impossible

for one brand-new American woman who meant well but had no idea what she

was getting into.

I thought we ate pretty carefully. But,

three times during our seven months in Egypt, I got roaring food poisoning.

I also was told that the primary killer of Egyptians in those days

was not heart attacks, or cancer, or auto accidents…, but gastro-intestinal

disease. I had a job to do, so

I couldn’t stop to be sick. Taisir and I would go across town, with me laid

almost horizontal in the front passenger seat--from which I’d occasionally

ask Taisir to pull over so I could barf out the door. And then we’d go on. Especially in summer heat and dust, with truck

exhaust in your face, this was not fun.

On

a totally separate level, I enjoyed taking Egyptians to eat in the United States.

On

Friday during the three-month program review in Marietta,

GA, senior Americans said they needed

a volunteer to take our Egyptian visitors up to Atlanta, and entertain them over the weekend.

As Sue was at our home in Ohio, I volunteered for

this fun and easy task.

As

our little motorcade made its way northward Friday afternoon, we passed

a McDonald’s sign. Rafaat, trying

to say this correctly, stammered-out, “Bill, I’m having a big…Mac…attack!”

Expressing

my appreciation for Rafaat’s attempt to grasp American culture, I guided

the motorcade into the McDonald’s parking lot.

The

generals and colonels were clueless. So

I suggested that, as a cultural experience, I order a Big Mac Meal for

each of us. Heads nodded positively.

In

those days, a Big Mac Meal came in a white foam-plastic box, much like

you get in restaurants today for doggie-bagging.

I carried our stack of boxes to a long table, and set one in front

of each Egyptian.

As

they opened their boxes and examined their Big Macs and fries, Major General

Rayan looked at me and said, “Bill, may I ask a question? Yours is a very big and rich country. So why do you Americans like to eat your food

out of plastic boxes?”

Pretty

good question….

Saturday

night, I decided to really impress these Egyptians with how wonderful

a restaurant in America

could be. I made a reservation

for us all at Pittypat’s Porch, which I remembered for things like its

awesome salad bar (an option that I never touched in Cairo…),

containing big trays of things like crab legs, shrimp, oysters, etc.

As

we worked our way along the salad bar, I commented that I thought this

was maybe the best one I’d ever seen in my life.

With no emotion of any kind, our Egyptian guests politely replied

that, yes, it is very nice.

I

was reminded, yet again, that their expectations of the USA were quite

open and to a great degree not yet colored-in.

I

felt much as I had the day an Egyptian colonel came into my office in

Headquarters, EAF, and stared at the snapshot of Sue & my little three-bedroom

house in Ohio, which was sitting empty during our seven months in Egypt.

A little touch of home, I’d pinned it onto the wall by my desk.

The colonel said, “Whose house is that?”

I said it was my home back in the USA. He pondered this a few seconds, and then said,

“No, it is not. Nobody but a minister

in the government has a house like that.” I couldn’t argue.

Speaking

of that office, GS-12 Deana Dennis, our supply expert from Warner-Robins Air

Logistics Center

at Robins Air Force Base, GA, and I shared it.

And we had a bathroom attached to our office. Pretty fancy…except that it needed a major cleaning,

and the toilet had no seat.

By

the way, the men’s latrine out in the C-130 squadron area appeared to

not have been cleaned at all since 1952, when the British departed. I found a similar situation much later in 1993,

at Saddam Hussein’s Habbaniyah Air Base west of Baghdad, where our UNSCOM inspection aircraft

landed. The smell in these Egyptian

and Iraqi latrines was a memory of a lifetime.

I

decided to do the gallant thing for Mrs. Dennis. I went deep into Cairo’s huge Khan el Khalili bazaar and found

a pink plastic toilet seat. So

proud of this capture, I then got a brass artisan to engrave me a small

plaque saying, “The Deana Dennis Memorial Toilet Seat.”

For all I know, it may still be there in Headquarters, Egyptian

Air Force. But it’s probably gone--along

with any seat….

Sleeping

(or not…)

Egyptian

office and social hours were, like the Mexican siesta system, wisely adapted

to hot afternoons in non-air conditioned working conditions and housing. So they slept twice.

I

arrived for work at Headquarters EAF about 7:30 in the morning, and just

about everyone departed there at 2:30 p.m.

Apparently, most of the Egyptian officers went home to sleep, unless

they were majors or below, which meant, as Rafaat told me, that they usually

couldn’t afford to own a car, and usually had to get a second job just

to make ends meet.

Being

an American tasked to work closely with our new Egyptian friends, I worked

not only the Egyptian six-day week Saturday-Thursday, but also the American

five-day week Monday-Friday…which meant that a typical work week for me

was all seven days.

And

the days were long. When Headquarters

EAF closed at 2:30, I hopped into the car with Taisir for the noisy, crowded,

stinking one-hour drive across the city to the U.S. Embassy, where Air

Attache Colonel Dolan kindly kept a desk for me, and where the many people

back in the Department of State, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Organization

of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Headquarters U.S. Air Force, Headquarters

Air Force Logistics Command (AFLC), and people at various AFLC air logistics

centers that supported the C-130--who also thought they were my bosses--could

send me messages.

These

messages usually asked for information or--since I was only a captain

and the C-130 program was apparently the biggest thing the U.S. Government

was doing with Egypt

at the time--telling me what to do. On

arrival at my embassy desk one day, I found 18 messages addressed to me. Of course, many wanted an answer.

So

Taisir often didn’t drop me off back in Heliopolis

(after another high-speed one-hour drive in the dark) until around 10

p.m. Sue was not thrilled. But my job had to get done, I took it very seriously

and apparently did it well, and Sue understood and put up with it.

Having

had a four-hour or so nap in the afternoon, Egyptians would then rise

as the sun was going down and the air cooled a bit, and do their “afternoon”

activities in the evening. Thus,

they normally ate dinner about the time Americans are going to bed, and

then went back to bed themselves around 2 or 3 a.m.

Thus,

it was a bit of a flexibility test when our wonderful landlord would knock

on our door at 11 p.m. hoping that I’d like to play dominoes, to which

I tried to always say “yes.” He

didn’t speak a word of English, and my Arabic was just enough to prevent

starvation in a restaurant, but with made-up sign language somehow we

managed to enjoy ourselves while playing dominoes.

The next day, I just yawned a lot.

Playing

Tourist

We

did take some days off to see some of the amazing sights in Egypt. Highlights are here in these photos.

Behind us in Port

Said is the base of what used to be a statue of Frenchman Ferdinand

de Lesseps, builder of the Suez Canal. His statue was pulled down by angry Egyptians

in 1956, when France,

Britain and Israel

invaded Egypt. President Eisenhower told the invaders to back

out, and they did.

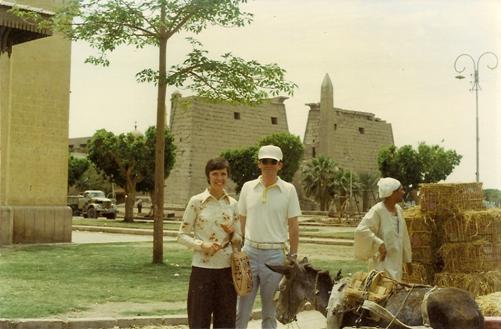

The Acropolis at Luxor,

which was a thousand years old when Rome

was built.

Wrapping

the Egypt

Experience

Our

seven months in Egypt

was a fascinating learning experience.

I learned to have great respect for the Egyptian people, and especially

to appreciate their warmth to guests in general and to Americans in particular.

I was very happy to see our little C-130

program successfully launch a larger and larger relationship between our

militaries that flourishes today. Indeed,

recall that, even before February 11th, 2011, when President

Mubarak resigned and handed power to the Supreme Council for the Armed Forces, Secretary Gates was saying,

as on February 8th, that the Egyptian Armed Forces had “acted

with great restraint and frankly they’ve done everything that we’ve indicated

we would hope that they would do.”

I

respected them…in 1976, when we barely knew anything about each other

at all.

When

I was sent back to Egypt

briefly in 1978 to take a look at the C-130 program and write an assessment

on how it was going, my baby-step initial Office of Defense Cooperation

functions in the Embassy were now accomplished by a real ODC led by a

brigadier general. He had a staff. When I went out to Headquarters EAF and the

C-130 squadron, I was told simply that, “Bill, after you left, the Americans

basically stayed under their air conditioners across town at the Embassy. We hardly ever see them.”

Our

Defense Attache, a major general, kindly asked me if I’d like to come

back. I said, “Sir, thank you,

but no thanks.” Back in Ohio, Brigadier General Edwards had assigned

me to be the lead action officer to create the new AFLC International

Logistics Center (ILC). And we

were very busy getting this big thing going.

Today, that ILC is blended

into the Air Force Materiel Command’s Air Force Security

Assistance Center,

still at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio, which, according to its current

fact sheet, “oversees system sales and support for more than 170 models

of aircraft, a fleet totaling more than 6,600. The center also orchestrates

AFMC product and logistics center support of security assistance needs

to 103 countries and seven NATO organizations, in addition to serving

as a ‘portfolio manager’ for foreign military sales within each country.

It also provides logistics support for numerous weapon systems, some dating

back to the 1940s, as well as modern ones.”

I know we made a positive difference in Egypt--literally

giving birth to what is now a big ongoing security assistance relationship.

And I know we made a major difference in creating that global International

Logistics Center. Both were very demanding assignments. Both felt good.

On the way home from Egypt in July 1977, we took a week-long Aegean

cruise out of Athens

on the Stella

Solaris.

Here, we’re in the amphitheater of ancient Ephesus

in Turkish Asia Minor. (note: the

Bible’s Book of Ephesians) The

water was so clear at the pier that, with the dawn sun rising on the other

side of the ship, we could see the entire hull of Stella Solaris under the water.

|